Speaking truth to power - Pride in the New Testament

Revd Dr Jonathan Tallon, Biblical Studies tutor at Northern Baptist College in Manchester, preached this sermon at our National Gathering on Saturday 10th June 2023. WATCH the closing communion service here [55mins]

“The powerful try to shame those who are LGBTQI. They encourage silence, hiddenness, don’t ask, don’t tell, sweep it under the carpet, be ashamed. Pride is an occasion to speak the truth frankly.”

JUNE is Pride Month, dedicated to celebrating LGBTQIA+ communities around the world. It’s also when we celebrate the anniversary of the founding of the first Open Table community in 2008.

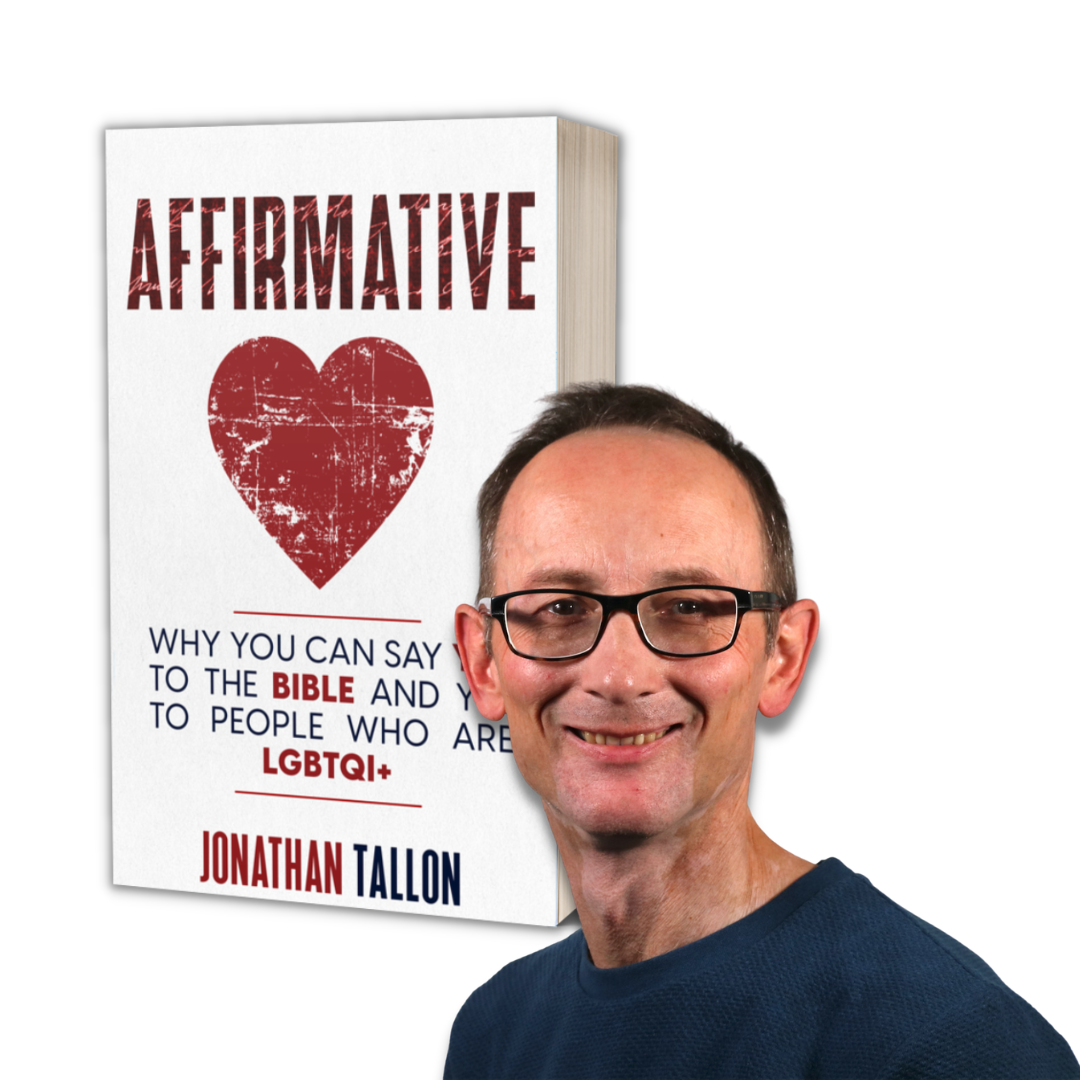

This year, at our national gathering in Cambridge on Saturday 10th June, our guest speaker was Revd Dr Jonathan Tallon, author of Affirmative: Why You Can Say Yes to the Bible and Yes to People Who Are LGBTQI+ and the website bibleandhomosexuality.org. He spoke about the understanding of ‘pride’ in the New Testament, with reference to Acts 4:1-31. This is what he wrote:

It’s a privilege to be invited here to preach at this Open Table Network national gathering. And it’s a privilege to be here during Pride month. And it’s Pride I want to talk about.

Now, I have to give a disclaimer here. I’m an ally, sat on the side-lines. I’ve only been to a couple of Pride events. I’m not involved in many campaigns. I tend to stick to my lane of talking about the Bible.

So it is with some trepidation that I’m speaking about Pride. I’m aware I’m doing it not as an insider, not someone for whom their identity can be a matter of life and death, but as a cis man who’s straight, white and privileged.

And so can I also beg your indulgence and forgiveness in advance? I may phrase things or say things inelegantly or inappropriately. If I do, please do come and let me know afterwards, so I can continue learning.

But I’m still going to talk about Pride.

Why celebrate Pride? And let’s start with the name. Pride. Because the word Pride can evoke some negative associations.

Haughtiness, arrogance. It is one of the seven deadly sins.

In fact, pride, hubris, is traditionally the worst of the seven deadly sins. The arrogance leads to all the other sins, and sets you up as better than everyone else.

So why celebrate Pride?

Because the opposite of pride is humility, and that’s a good thing. We know that’s a good thing. Jesus tells us that’s a good thing: blessed are the meek. All who exalt themselves will be humbled, and all who humble themselves will be exalted.

Franklin Graham, the conservative American commentator, asked why we don’t celebrate humility instead.

So why celebrate Pride?

Some words can have more than one opposite. The opposite of right is wrong. Except when it’s left.

The opposite of sweet is sour. Except when talking about wine, when it’s dry. Whose opposite is usually wet.

So here’s another opposite of pride: shame.

Shame is both individual and social. It’s that churning feeling in the pit of your stomach when you feel that you’ve done something wrong or feel embarrassed or humiliated. And it’s the stigma that others treat you with.

And it’s not, in itself, a bad thing. Some things, we should feel ashamed about, and be shamed for.

In some areas, I find myself longing for more shame. I look at what some politicians have done, and wonder, do they feel no shame? None? Because there is no hint of it. And in the western world we have a man running for US president who assaults women sexually, who incites insurrection – and seems to show no shame.

I’m not having a go at shame here.

But it’s worth noting the effect of shame, when it is present.

It leads to avoidance. It leads to silence. It leads to hiding away.

In the majority culture in Britain, shame is not a big value - less than perhaps it was Victorian times, when there was a premium on respectability.

And here is where I segue to the Bible reading. Because New Testament times were more like the Victorian world. In the social sciences, it would be described as an honour-shame culture.

Shame is a big deal in the New Testament. We sometimes miss it, because we don’t have the same emphasis on those values.

Here’s a quick example. When we think about the crucifixion, and the suffering of Jesus, we tend to focus on the physical pain he was in. The nails, the flogging. You can see that in the Mel Gibson film, The Passion of Christ, which focused on that pain in close up. And that’s a feature of Western theology.

But I had a Coptic teacher at one time, that’s the Egyptian church, similar to the Orthodox church, and he said that in Eastern Christianity, it was the shame of the cross that was important. Jesus was someone who was publicly humiliated and shamed: stripped of his clothes, scorned, whipped, made a spectacle before everyone; dying a shameful death.

And that’s how the Roman authorities worked. You rebelled, you got a shameful, painful, public death - usually a punishment for slaves who didn’t know their place.

And the effect was to silence dissent. To silence rebellion. To keep people in their place.

And the Acts of the Apostles is the story of how that didn’t work.

The followers of Jesus, meant to be cowed into silence, do the opposite. The narrative we heard today [Acts 4:1-31] is one example.

Peter and John are passing by one of the temple gates, and heal, in the name of Jesus, a man who had been lame since birth. They then tell the crowd about Jesus. We join the account when the temple police turn up, and arrest them both, slinging them in jail overnight because it was late.

The next morning, they’re brought in front of some type of council, led by Annas and Caiaphas, and they’re interrogated.

In response, Peter speaks the truth.

He tells them the truth about Jesus, and the truth of what he and John have experienced.

The authorities decide that Peter and John should be told to be silent. Hide the story away.

Peter?

‘Whether it is right in God’s sight to listen to you rather than to God, you must judge; for we cannot keep from speaking about what we have seen and heard.’ - Acts 4:19-20.

He keeps telling the truth, frankly.

Sometimes shame is good. But sometimes it is bad.

It is used to hide the truth. It is used by the powerful against the powerless. It is used to control.

But the covering of shame begins to crack when the truth is spoken frankly.

And the covering of shame begins to crack when the truth is spoken publicly.

Peter speaks in the temple amongst the people. Peter speaks in the council amongst the powerful. Peter promises to keep speaking the truth, come what may.

The covering of shame begins to crack when the truth is spoken courageously.

Peter speaks when arrested. Peter speaks when being warned. Peter speaks despite being offered don’t ask, don’t tell.

Speaking the truth frankly, publicly and courageously.

There’s a word for that in the New Testament.

I teach Greek, and occasionally critique sermons, and I always say not to include Greek in sermons. But rules are made to be broken…

I don’t know if you noticed, but in verse 13 there’s a reference to the ‘boldness’ of Peter and John.

To translate is to betray, as an old saying goes. The translators have made a good choice. But it’s limited.

The Greek word translated as ‘boldness’ is parrhesia.

And it’s a word you can find throughout Acts, and also in the letters of the New Testament.

The early church considered it a great virtue.

But what is parrhesia?

It is speaking truth to power.

It is speaking the truth frankly. It is speaking the truth publicly. It is speaking the truth courageously.

And in Acts 4:29, we find that this is what the church prayed for:

‘And now, Lord, look at their threats, and grant to your servants to speak your word with all boldness…’.

With all parrhesia. And this is what, empowered to speak with parrhesia by the Holy Spirit, they did.

What I want to suggest to you is that celebrating Pride is parrhesia.

The powerful try to shame those who are LGBTQI. They encourage silence, hiddenness, don’t ask, don’t tell, sweep it under the carpet, be ashamed.

Pride is an occasion to speak the truth frankly.

To tell the world we humans are diverse. That love is not confined. That God’s children are wonderful in their variety, and that variety is to be celebrated, not hidden.

Pride speaks that truth frankly, not pretending that everyone is cis and straight.

Pride speaks that truth publicly. It is not hidden. It cracks open the cover of shame and exposes truth to the glorious light.

Pride speaks that truth courageously.

From its beginnings in 1970, on the first anniversary of the Stonewall uprisings after continued harassment, it has been a brave speaking of truth to power. And sadly, after more than fifty years, you still need bravery, still need courage, in a context that has seen a toxic moral panic whipped up against trans people, and spreading to all of the LGBTQI communities.

This month, many of you will take part in Pride marches and Pride activities. As you do, know that you embody that virtue valued by the early church of parrhesia, speaking the truth of LGBTQI people to power, frankly, publicly and courageously.